The arrest of a sitting president by a foreign power is among the most consequential acts contemplated under international law.

It tests not merely the legality of a single operation, but the durability of a rules-based international order grounded in sovereignty, restraint, and multilateral cooperation.

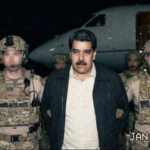

The recent arrest of Venezuela’s president presents precisely such a test. The central issue is not whether the Venezuelan government is democratic, legitimate, or morally defensible.

International law does not allocate legality on the basis of political approval or disapproval.

The relevant inquiry is narrower and far more consequential: Was the arrest compatible with the international legal framework governing the use of force, jurisdiction, and head-of-state immunity? A compelling legal case can be made that it was not.

Sovereignty and the Prohibition on the Use of Force The modern international legal order rests on the United Nations Charter.

Article 2(4) prohibits states from using force against the territorial integrity or political independence of another state, a rule widely recognized as jus cogens, a peremptory norm from which no derogation is permitted.

Only two exceptions exist. The first is individual or collective self-defense in response to an armed attack, as provided under Article 51.

The second is enforcement action authorized by the United Nations Security Council under Chapter VII. Outside these narrowly defined circumstances, the use of force on the territory of another sovereign state is unlawful.

An arrest operation conducted by foreign military or security forces inside Venezuela, without the consent of Venezuelan authorities and absent Security Council authorization, is difficult to reconcile with these principles.

Even a domestic criminal indictment issued by a foreign court regardless of the seriousness of the alleged offenses does not supply a lawful basis for extraterritorial enforcement by force.

International law draws a clear distinction between jurisdiction to prescribe law and jurisdiction to enforce it.

While states may assert criminal jurisdiction over certain extraterritorial conduct, they may not enforce that jurisdiction on the territory of another sovereign state without that state’s consent.

Head-of-State Immunity

The legal concerns are compounded by the doctrine of personal immunity for sitting heads of state. Under customary international law, heads of state, heads of government, and foreign ministers enjoy immunity ratione personae from arrest and criminal prosecution by foreign states while in office.

This immunity is procedural rather than substantive: it does not extinguish criminal responsibility but defers it until the individual leaves office or appears before a competent international tribunal.

The International Court of Justice affirmed this principle in the Arrest Warrant case (Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Belgium), holding that even allegations of serious international crimes do not permit unilateral arrest by a foreign state while such immunity applies. While there is ongoing debate about exceptions for international crimes such as genocide or crimes against humanity, these discussions have largely concerned proceedings before international courts.

No settled rule of international law authorizes a state to disregard head-of-state immunity through unilateral force on foreign soil.

The Limits of Legitimacy Arguments

Some have argued that Venezuela’s president lacks democratic legitimacy and therefore does not benefit from the protections ordinarily afforded to heads of state.

Such arguments may carry political appeal, but they carry limited legal weight.

International law is intentionally conservative on questions of recognition and legitimacy. States routinely engage with governments they regard as illegitimate or repressive precisely to prevent political judgments from becoming legal justifications for intervention.

Allowing unilateral determinations of legitimacy to justify cross-border arrests would erode the predictability and stability that international law is designed to preserve.

A Dangerous Precedent

The broader concern is systemic. If powerful states may enforce their criminal laws by force against sitting leaders of weaker states, without multilateral authorization, the prohibition on the use of force risks becoming contingent rather than categorical.

Such a precedent would not remain confined to a single case or region. It would invite reciprocal actions, intensify geopolitical fragmentation, and weaken the authority of international institutions tasked with maintaining peace and accountability.

None of this suggests that heads of state are above the law. Accountability for international crimes is both legitimate and necessary.

But international law insists that accountability be pursued through lawful multiteral processes, international tribunals, or domestic proceedings consistent with established jurisdictional limits and immunities.

Law, Power, and the Future of the International Order

The arrest of Venezuela’s president thus poses a stark question for the international community: Is international law a binding framework that constrains even the most powerful states, or is it a flexible instrument applied selectively?

If the latter view prevails, the consequences will extend far beyond Venezuela. The erosion of legal restraints on the use of force would mark a significant departure from the post-1945 international settlement, shifting the global order closer to one governed by power rather than law.

The stakes, therefore, are not merely Venezuelan or American. They are global.

- President Commissions 36.5 Million Dollars Hospital In The Tain District

- You Will Not Go Free For Killing An Hard Working MP – Akufo-Addo To MP’s Killer

- I Will Lead You To Victory – Ato Forson Assures NDC Supporters

Visit Our Social Media for More