Heads of state of Mali’s Assimi Goita, Burkina Faso’s Captain Ibrahim Traore and Niger’s General Abdourahamane Tiani walk together

More than six decades after political independence swept across the African continent, many African states still grapple with a fundamental dilemma: how to govern in a way that reflects the will, culture, and aspirations of their people while resisting external domination. The early euphoria of independence soon gave way to fragile states, cyclical coups, externally engineered democracies, and governance structures that remain deeply entangled in the legacies of colonial administration. Although constitutions were rewritten and parliaments formed, the substance of African political and economic independence remained compromised, largely controlled by foreign aid regimes, Bretton Woods institutions, and multinational corporate interests.

Governance systems across the continent have thus often been imitative rather than indigenous, with many African countries adopting Western-style liberal democracies—parliamentary or presidential—modelled on either the Westminster or French systems. Though widely praised for their emphasis on electoral competition, separation of powers, and civil liberties, these systems have struggled to deliver inclusive development in Africa, frequently resulting in elite capture, policy paralysis, corruption, and low public trust in political institutions (Gyimah-Boadi, 2017; Cheeseman, 2015). As a result, the promised dividends of liberal democracy have remained elusive for many African citizens, who increasingly question whether the democratic process alone is sufficient to guarantee prosperity and sovereignty.

Against this backdrop, a remarkable yet underexplored shift has occurred in the Sahel region of West Africa. Over the past three years, countries such as Mali (2021), Burkina Faso (2022), and Niger (2023) have undergone military-led transitions that not only removed entrenched political elites but also directly challenged the legitimacy of externally imposed governance frameworks. Notably, these transitions took place without widespread bloodshed and have received significant popular support, particularly among youth, civil society actors, and disenfranchised rural populations. What is emerging in these countries is a hybrid, sovereignty-driven governance model that seeks to blend the strengths of indigenous African political traditions, the strategic planning discipline of military command, and aspects of modern technocracy, while systematically rejecting foreign control, debt dependency, and exploitative resource arrangements. This nascent framework—what may be termed the Sahelian Transition Model (STM)—is gaining scholarly and policy interest not because it is perfect, but because it represents a bold attempt to reimagine African governance on African terms.

In a world where democracy has increasingly been instrumentalised by geopolitical interests, many African governments remain vulnerable to regime change, conditional aid, manipulated elections, and information warfare. As global powers compete for strategic influence in Africa—via military bases, resource contracts, and digital infrastructure—the question of what constitutes genuine sovereignty has gained renewed urgency. Leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah, Muammar Gaddafi, Thomas Sankara, and Nelson Mandela all raised early alarms about Africa’s dependency syndrome and the weaponisation of global governance standards to serve neocolonial interests. Nkrumah (1965) famously warned of “flag independence” without economic control. Gaddafi envisioned pan-African monetary unions and collective security mechanisms.

Sankara emphasised resource nationalisation and self-reliance as prerequisites for dignity, while Mandela, though more reconciliatory in tone, remained deeply aware of the structural limitations that global finance and post-apartheid economic compromises imposed on true liberation. Though these leaders were often met with resistance and, in some cases, violently silenced, their philosophies endure as symbolic reference points in Africa’s long-standing quest for holistic emancipation. The STM appears to echo this historic ambition. It offers a model that confronts the dominance of Western governance templates while reclaiming political and policy space for indigenous wisdom, communal justice, and economic self-determination.

This article explores the Sahelian Transition Model as a potential alternative to Africa’s current governance paradigms. The objective is not to idealise military interventions nor to endorse any form of autocracy, but rather to critically assess whether this model contains valuable insights and replicable structures that can inform governance reforms across the continent. The paper undertakes a comparative analysis of the STM and global governance systems, including liberal democracies, monarchies, and autocracies. It further analyses the core components of the STM, such as resource nationalism, debt rejection, popular consultation, and security-led development. The study includes a detailed case study of Burkina Faso under Captain Ibrahim Traoré and identifies both the structural innovations and the latent risks within the model. Lastly, it reflects on the philosophical and strategic relevance of African forerunners like Nkrumah, Gaddafi, and Mandela in shaping this new trajectory.

This inquiry is framed by several critical research questions: Does the Sahelian Transition Model represent a viable governance alternative for Africa beyond Western liberal democracy? Can a model that emphasizes sovereignty, resource control, and communal legitimacy provide better outcomes for African populations? And what lessons can be drawn from countries attempting this model, particularly in terms of how it may be adapted to ensure accountability, resilience, and stability? In an era where Africa’s political systems are still largely designed by donors, monitored by external observers, and validated through metrics developed outside the continent, this study offers a timely and necessary intervention. It aims to open intellectual and policy space for an Africanized governance discourse—one that acknowledges complexity, embraces functional hybridity, and reclaims autonomy from both conceptual and structural subjugation. The STM, though young and unfinished, invites African scholars, policymakers, and citizens to revisit the foundational question: can Africa finally govern itself in ways that are both authentic and effective?

- Governance Systems in Comparative Perspective

- Conceptualizing Governance: From Global Norms to Local Realities

Governance, broadly defined, refers to the systems, institutions, and processes through which authority is exercised and decisions are made for the public good (World Bank, 1994). However, what constitutes “good governance” is deeply contested and often shaped by historical context, ideological inclinations, and geopolitical interests. In post-colonial Africa, the prevailing orthodoxy of “good governance” has largely been imported—measured by indices like free elections, rule of law, decentralization, and civil liberties, often without adequate attention to local socio-political dynamics (Hyden, 2006; Mkandawire, 2001). This literature review critically evaluates several prominent governance systems globally and contrasts them with Africa’s pre-colonial traditions and emerging Sahelian frameworks.

- Western Liberal Democracy and Its African Adaptations

Rooted in the Enlightenment philosophies of Locke, Rousseau, and Montesquieu, liberal democracy emphasizes the separation of powers, competitive elections, free press, and individual rights. In theory, this model offers checks against tyranny and promotes accountability. In practice, its implementation in Africa has been uneven and, at times, dysfunctional. Post-independence African democracies, especially those modeled after British and French systems, have often suffered from patronage politics, ethnic clientelism, low civic trust, and incomplete state formation (Cheeseman, 2015; van de Walle, 2003). Although countries like Ghana, Senegal, and Botswana have experienced relative democratic stability, many others such as Kenya, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo have witnessed democratic erosion, electoral violence, or constitutional manipulation. Moreover, democracy aid and election monitoring by Western institutions—while intended to support democratization—have often reinforced externally oriented legitimacy at the expense of internal ownership. A recurring criticism is that Western liberal democracy, as applied in Africa, prioritizes form over function—fixating on elections while ignoring state capacity, justice delivery, and developmental outcomes (Mamdani, 1996).

- Authoritarian Governance: The Case of Russia and China

Authoritarian systems—where power is concentrated in a central authority and dissent is limited—have evolved differently across contexts. In Russia, Vladimir Putin’s model of sovereign democracy emphasizes national pride, state capitalism, and security centralization. Though the system ensures political stability and national coherence, it is widely criticized for stifling civil liberties, suppressing opposition, and fostering corruption (Gel’man, 2015). In contrast, China has demonstrated a unique form of authoritarian meritocracy. Since the 1978 reforms, China’s one-party system has lifted over 800 million people out of poverty through a blend of market liberalization and strict political control (World Bank, 2022). While Western critics highlight China’s human rights record and lack of electoral participation, others argue that its technocratic efficiency, policy continuity, and long-term planning offer governance lessons, particularly for developing nations with fragile institutions (Bell, 2015). Africa’s flirtation with authoritarianism—especially under regimes like Mobutu in Zaire or Mengistu in Ethiopia—was more extractive than developmental. However, the rise of technocratic-authoritarian hybrids in places like Rwanda and Ethiopia has revived debates about whether centralized models can deliver inclusive development if paired with civic accountability.

- Monarchical Hybrids and Developmental Absolutism: Gulf and European Variants

The monarchies of the Gulf—such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE—present an intriguing blend of hereditary rule and modern technocratic governance. Despite the absence of electoral democracy, these states have achieved high levels of infrastructure development, human development index (HDI) scores, and strategic resource management, thanks to oil revenues and centralized planning (Hertog, 2010). Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, spearheaded by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, aims to diversify the economy, reduce oil dependence, and modernize the state. Yet, critics highlight theocratic repression, lack of women’s rights, and migrant labor abuses as critical failings (Human Rights Watch, 2022). The UAE, particularly Dubai, has emerged as a global innovation and logistics hub, combining top-down efficiency with global capital flows. Its governance model—non-democratic but highly responsive—suggests that institutional effectiveness may not always correlate with electoral pluralism. In Europe, constitutional monarchies like the UK maintain symbolic royalty while entrusting governance to elected parliaments. This system fosters stability, though in recent years it has faced legitimacy crises—such as those surrounding Brexit, Scottish independence, and royal controversies (Bogdanor, 2021).

- Indigenous African Governance Traditions: A Forgotten Asset?

Long before colonialism, African societies had developed robust governance systems—ranging from the consensus-driven councils of elders among the Igbo and Akan, to the centralized kingdoms of the Zulu, Mali Empire, and Ashanti Confederacy. These systems emphasized:

- Moral leadership (not just legal-rational authority)

- Restorative justice (not punitive codes)

- Collective consensus (not majoritarian rule)

- Spiritual accountability (often tied to ancestral and religious ethics)

Colonialism either destroyed or co-opted these systems, reducing them to “traditional authorities” devoid of their former sovereignty. Scholars like Mahmood Mamdani (1996) argue that post-colonial African states inherited bifurcated authority structures—modern bureaucracies for urban elites and distorted customary systems for rural populations—leading to chronic legitimacy crises. Efforts to revive these traditions—through decentralized chieftaincy reforms, customary law integration, or participatory budgeting—have been partial and often symbolic. Yet, the Sahelian Transition Model appears to be one of the few contemporary experiments seeking to recenter these indigenous values within a modern state apparatus.

- Pan-African Forerunners and the Quest for Self-Determined Governance

The search for African sovereignty has been championed by visionary leaders who defied Western domination and proposed alternative governance paradigms:

- Kwame Nkrumah emphasized continental unity, state-led development, and economic independence. His concept of “neo-colonialism” remains influential in explaining Africa’s external entanglements (Nkrumah, 1965).

- Muammar Gaddafi envisioned a United States of Africa, proposed an African monetary fund, and emphasized grassroots direct democracy through local councils. His downfall was, in part, a reflection of geopolitical resistance to such bold aspirations.

- Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso nationalized land and resources, reduced ministerial privileges, and promoted local production. He remains an icon of African integrity, assassinated for daring to question the post-colonial order.

- Nelson Mandela, though largely aligned with liberal democratic values, recognized the tension between reconciliation and economic justice. His post-apartheid policies were often constrained by global financial structures and domestic elite interests.

These figures reveal that Africa has long possessed the intellectual and political capacity to design its own governance systems—but has lacked the geopolitical space and institutional sovereignty to implement them sustainably.

- Toward a Synthesis: The Case for Functional Hybridity

What emerges from the literature is that no single governance system offers a panacea. Liberal democracy offers political participation but often lacks coherence in fragmented societies. Authoritarian models deliver efficiency but suppress freedoms. Monarchies may offer cultural continuity but restrict pluralism. Indigenous systems emphasize community but may struggle with modern complexities. The Sahelian Transition Model, though young and still forming, proposes a functional synthesis—rooted in popul ar legitimacy, cultural authenticity, resource sovereignty, and strategic modernization. It demands academic and policy attention not as a rejection of democracy, but as a redefinition of democracy in African terms—one that reclaims the agency to govern from within, rather than to be governed from without.

- The Sahelian Transition Model (STM): Origins and Principles

- Political Genesis of the STM: Resistance, Restoration, and Realignment

The Sahelian Transition Model (STM) did not arise from an academic blueprint or ideological manifesto. It emerged, rather, from a complex mix of popular disillusionment, elite failure, regional insecurity, and geopolitical awakening in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger—three countries long seen as peripheral players in the global political economy. By the early 2020s, each had suffered from a convergence of governance breakdown, jihadist insurgency, economic stagnation, and external military entanglements, especially involving France, the United Nations, and other Western forces.

The catalyst for change was not elections or donor reforms, but rather popularly supported military takeovers—beginning with Mali (2021), followed by Burkina Faso (2022), and Niger (2023). Far from the conventional coups of the Cold War era, these transitions were distinguished by several characteristics:

- Minimal or no bloodshed during power transfer

- Immediate public support and civic celebrations

- Expulsion of foreign troops or ambassadors viewed as neocolonial

- Rapid policy redirection toward national resource control, rural security, and debt resistance

What emerged was not simply a new regime, but a new philosophy of statehood—one rooted in sovereignty, cultural authenticity, and functional governance beyond imported doctrines.

- Foundational Tenets of the STM

The Sahelian Transition Model is not a fixed or homogenous system; it is still unfolding. However, its core principles and structural innovations reflect a deliberate departure from Western liberal frameworks in favor of a hybrid governance architecture, built on five main pillars:

1. Popular Sovereignty Through Direct Legitimacy

Rather than seeking international validation through elections organized by foreign observers, STM regimes claim legitimacy directly from the population, particularly through youth mobilizations, traditional authorities, and rural community engagement. Decision-making is increasingly filtered through People’s Assemblies and consultative dialogues rather than elite-centric parliaments.

2. Resource Nationalism and Economic Reclamation

STM states have prioritized the reassertion of control over natural resources—including uranium (in Niger), gold (in Burkina Faso), and phosphate (in Mali). Many contracts signed with multinational corporations under previous administrations are being reviewed, renegotiated, or revoked. The objective is not isolationism, but equitable partnership anchored in sovereignty. Revenue from resource extraction is being redirected into local infrastructure, military self-sufficiency, and agricultural revitalization. For example, Burkina Faso under Captain Ibrahim Traoré has implemented policies to retain 80% of gold revenue locally, while banning the uncontrolled export of raw mineral ore.

3. Debt Rejection and Fiscal Independence

One of the most radical departures from IMF and World Bank orthodoxy is the STM’s stance on foreign debt. These governments have refused to pay debts deemed illegitimate or neo-colonial in nature, labeling them as instruments of perpetual dependency. Instead, they are pursuing bilateral funding with nations that do not impose ideological conditionalities, such as Russia, Turkey, China, and emerging Global South alliances. In 2023, Mali announced a complete suspension of external debt servicing, redirecting those funds into rural education and domestic industrialization programs.

4. Security-Led Development and Territorial Reclamation

Unlike models that separate state-building from security, the STM integrates security as a developmental tool. The armed forces are not only defending against insurgents, but also delivering social services, reopening rural roads, and coordinating community development. The doctrine is that without security, there is no education, no farming, no statehood. Military professionalism is being redefined not as repression, but as nation-building, with explicit mandates to protect and develop. This is especially visible in joint operations to reclaim “ungoverned territories” and repopulate areas previously lost to extremist violence.

5. Cultural, Spiritual, and Religious Decolonization

Beyond material sovereignty, the STM emphasizes intellectual and spiritual emancipation. This includes the promotion of local languages in public administration, the revival of African-centric education, and the rejection of Western cultural hegemony in law, media, and values.

Educational curricula are being revised to reflect Islamic-African heritage, traditional conflict resolution systems, and indigenous epistemologies. The STM is not anti-Western; rather, it is post-Western—seeking to redefine African identity on terms free of mimicry or subordination.

- Institutional Architecture of the STM: An Evolving Framework

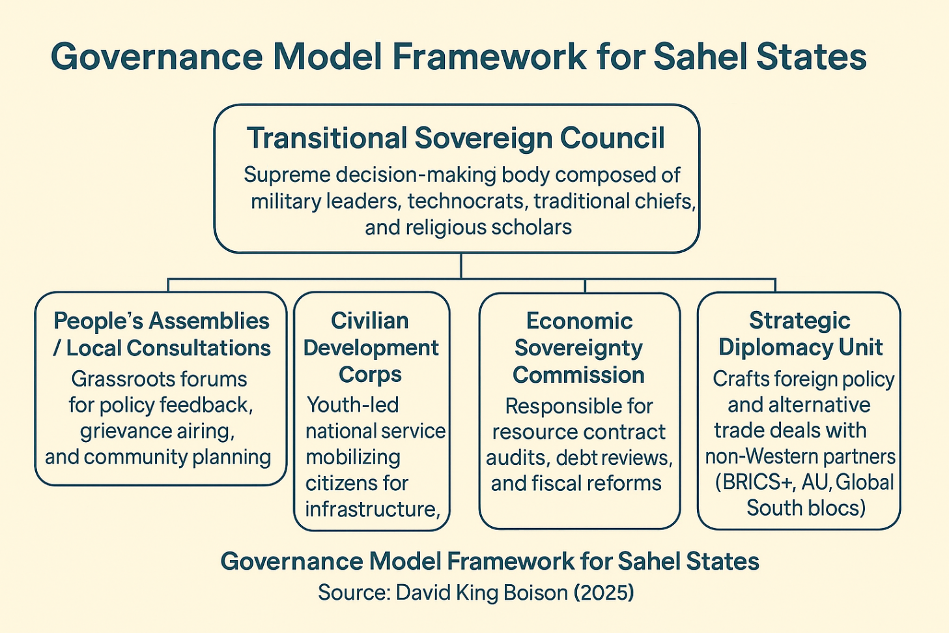

Although each country’s experience differs, a general institutional prototype is emerging:

| Institution | Role and Description |

| Transitional Sovereign Council | Supreme decision-making body composed of military leaders, technocrats, traditional chiefs, and religious scholars |

| People’s Assemblies / Local Consultations | Grassroots forums for policy feedback, grievance airing, and community planning |

| Economic Sovereignty Commission | Responsible for resource contract audits, debt reviews, and fiscal reforms |

| Civilian Development Corps | Youth-led national service mobilizing citizens for infrastructure, health, and environmental projects |

| Strategic Diplomacy Unit | Crafts foreign policy and alternative trade deals with non-Western partners (BRICS+, AU, Global South blocs) |

Rather than adopting ready-made institutions, the STM is reconstructing governance from the ground up, combining security, civic engagement, and economic autonomy under a unifying national mission.

- A New Social Contract: From Passive Subjects to Active Citizens

Perhaps the most striking feature of the STM is its shift in the political consciousness of the governed. Citizens are no longer treated as passive voters courted during elections but as co-owners of the national project. Political participation is not limited to party affiliation but expressed through communal consultation, volunteerism, defense efforts, and agricultural revitalization. This represents a revival of the communal ethic—a value system embedded in African governance traditions, where leadership is service and citizenship is responsibility.

- Philosophical Continuity with Pan-Africanism and African Socialism

While the STM is contemporary in form, it is deeply rooted in the philosophical soil of African emancipation. Its tenets echo the ideological lineage of:

- Kwame Nkrumah – whose “political kingdom” vision demanded control over African resources and industrial policy

- Muammar Gaddafi – who sought to unite Africa economically and militarily against Western manipulation

- Thomas Sankara – whose policies on land reform, anti-corruption, and women’s empowerment continue to inspire STM leaders

- Nelson Mandela – who, although conciliatory in politics, consistently spoke about the economic dimensions of freedom

This philosophical heritage positions the STM not as a rupture, but as a resurgence of unfinished liberation, now shaped by 21st-century realities. The Sahelian Transition Model is neither utopian nor conclusive. It is a living political experiment, born out of regional instability but reconfigured into a bold, pragmatic, and culturally resonant model of governance. While challenges remain—ranging from external sanctions to internal coordination—the STM demonstrates that Africa need not borrow its legitimacy, outsource its development, or mortgage its dignity. It offers a compelling proposition: that governance, to be sustainable in Africa, must be sovereign in philosophy, inclusive in practice, and grounded in reality.

- Comparative Analysis: The STM Versus Global Governance Systems

- Rethinking the Metrics of Governance

Most comparative governance literature evaluates systems based on liberal criteria such as free and fair elections, press freedom, civil liberties, and party pluralism—measured by indices like Freedom House, Polity IV, or the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index. While important, these metrics often fail to capture contextual realities in Africa, where formal institutions may exist but lack substance, legitimacy, or performance capacity.

To provide a more functional and Afrocentric analysis, this section adopts four key criteria to evaluate governance systems:

- Public Legitimacy and Participation

- Economic Sovereignty and Resource Control

- Institutional Stability and Responsiveness

- Cultural and Historical Coherence

The STM is then measured against liberal democracy, authoritarian capitalism, and hybrid monarchies, with reflections on how each system empowers or disempowers the governed.

- Public Legitimacy and Participation

Liberal democracies champion electoral participation, but in many African contexts, elections have become ritualized competitions marred by rigging, ethnicity, elite capture, and foreign interference. Voter apathy is rising, as electoral cycles rarely lead to meaningful transformation (Cheeseman, 2015). Authoritarian models (e.g., China, Russia) suppress dissent but maintain legitimacy through performance—economic growth, nationalism, or historical continuity. However, political alienation remains high among marginalized groups. Monarchies in the Gulf (e.g., UAE, Saudi Arabia) derive legitimacy from dynastic loyalty, religious authority, and development delivery. Yet, political participation is restricted to consultative forums without legislative autonomy. In contrast, the STM gains legitimacy through direct engagement—military-civilian alliances, traditional leaders, youth councils, and communal consultations. Participation is not electoral alone; it includes community mobilization, security defense, and cooperative development. Citizens are repositioned as co-authors of national renewal, not mere ballot participants.

- Economic Sovereignty and Resource Control

Liberal democracies in Africa have often operated under IMF conditionalities, debt dependency, and unbalanced contracts with extractive corporations. Despite privatization and deregulation, many countries remain economically subordinate. China and Russia have demonstrated stronger resource control and state-guided capitalism. However, their focus is nationalistic and not easily replicable in diverse, post-colonial African states. Gulf monarchies exercise tight control over oil and land but rely heavily on expatriate labor and are vulnerable to commodity shocks. Nonetheless, they have built sovereign wealth funds, reinvesting resource rents into future infrastructure. STM countries are assertively reclaiming control over strategic resources, renegotiating or cancelling exploitative contracts, and prioritizing local beneficiation over raw exports. Mali, for instance, suspended foreign mining licenses pending legal audit. Burkina Faso redirected gold earnings toward food security and self-defense programs. In this domain, STM surpasses other African governance models by rejecting neocolonial financial entanglements and emphasizing resource-backed sovereignty.

- Institutional Stability and Responsiveness

Western democracies pride themselves on institutional checks and balances, but in Africa these structures are often hollowed by executive dominance, politicized judiciaries, and compromised legislatures. Elections may change faces, but governance remains inert. Authoritarian regimes offer rapid decision-making but lack accountability, often responding with force rather than reform when challenged. Monarchies tend to be stable but slow-moving and often unreceptive to modern civic demands. The STM introduces a new model of responsive governance through transitional bodies—such as Sovereign Councils and Economic Commissions—guided by military discipline but informed by grassroots feedback mechanisms. Security operations are paired with social services, while policy is adapted in real time to meet changing community needs. This blend of efficiency and consultative governance gives the STM high adaptive capacity, especially in fragile post-conflict settings.

- Cultural and Historical Coherence

Most imported governance systems ignore Africa’s complex cultural inheritance—including its communalism, spiritual governance, and extended family structures. Liberal systems prioritize individualism and legalism, often clashing with community-based ethics. Authoritarian and monarchic systems may be internally coherent but lack resonance in African plural societies.

The STM stands out for its alignment with African historical traditions:

- Leadership is seen as a moral duty, not a personal entitlement.

- Communal consultation replaces adversarial politics.

- Customary norms inform dispute resolution.

- Indigenous languages and religious values are central to identity formation.

In this respect, STM reclaims governance as an extension of African civilization, not as an imposition of foreign models.

- Comparative Summary Table

| Criteria | Liberal Democracy (Africa) | Authoritarian Capitalism (Russia/China) | Gulf Monarchies | Sahelian Transition Model (STM) |

| Public Legitimacy | Weak, election-centric | Moderate, performance-based | High (dynastic/religious) | Strong, grassroots-led |

| Resource Control | Low (donor dependency) | High (state capitalism) | Very High | High and rising |

| Institutional Responsiveness | Low to moderate | Moderate but repressive | Moderate | High (security + civic response) |

| Cultural/Historical Coherence | Low | Low | Medium | High (indigenous integration) |

- Why STM Appears More Contextually Appropriate for Africa

The STM does not reject democracy, but reconstructs it from below—prioritizing sovereignty, justice, and development over mere formalism. It integrates the collective ethic of traditional governance, the organizational discipline of military command, and the strategic pragmatism of developmental states, without replicating their authoritarian pitfalls. In many ways, it responds to the call of Pan-African visionaries—who for decades warned that Africa cannot liberate its people through borrowed systems. As the continent searches for governance systems that work for its realities, the STM presents a rare endogenous alternative.

- Case Study: Burkina Faso Under Captain Ibrahim Traoré

- Crisis, Coup, and Change

Burkina Faso, a landlocked West African nation with a history of political turbulence, emerged in the global spotlight in October 2022 when Captain Ibrahim Traoré, a young and previously little-known officer in the Burkinabè armed forces, led a bloodless coup that ousted the transitional government of Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Damiba. This was the second military takeover in less than nine months, signaling deep-rooted governance failures, growing insecurity, and widespread disillusionment with Western-backed democratic experiments. In the time Traoré assumed power, nearly 40% of Burkina Faso’s territory was under insurgent control (primarily linked to jihadist networks), over two million citizens were internally displaced, and key gold mining regions—a cornerstone of the national economy—had been infiltrated or abandoned due to violence (UNHCR, 2022; International Crisis Group, 2023). Yet within a year, the new leadership had reclaimed significant portions of territory, strengthened civic-military cooperation, expelled foreign forces, and realigned national policy around sovereignty, self-reliance, and grassroots governance. The unfolding governance reforms in Burkina Faso serve as a practical manifestation of the Sahelian Transition Model (STM).

- Sovereignty in Action: Rejecting External Control

One of the most defining features of Traoré’s administration has been its open repudiation of neocolonial influence, especially from France. Within months of taking office, Traoré’s government:

- Ordered the withdrawal of French troops from Burkina Faso

- Terminated military cooperation agreements signed under previous governments

- Shut down French-owned media outlets accused of propagandist narratives

- Announced a review of all foreign mining contracts signed under questionable terms

This assertive posture signaled a paradigm shift in foreign relations, drawing sharp criticism from Western diplomats but widespread applause from Burkinabè citizens and pan-Africanist movements across the continent. The new leadership has since pivoted toward non-traditional partners such as Russia, Iran, Turkey, and China, forging diplomatic and security ties based on what Traoré calls “mutual dignity and interest,” not ideological alignment.

- Economic Nationalism and Resource Reclamation

Burkina Faso is Africa’s fourth-largest gold producer, yet its people have long remained impoverished, with over 40% of the population living below the poverty line (World Bank, 2022). Under the STM approach, Traoré has prioritized resource nationalism through:

- Audit and renegotiation of mining concessions, many of which granted up to 90% profit to foreign entities

- A new directive to ensure 80% of gold revenue remains within national borders

- Establishment of a state-controlled gold purchasing agency, circumventing offshore trading platforms

- Investments in artisanal mining cooperatives to empower rural communities

In a widely reported case, the government seized illegally exported gold and reinvested the proceeds into military logistics and emergency food distribution (Jeune Afrique, 2023). These measures represent a strategic break from the extractive-export model, favoring a sovereign industrial base with long-term beneficiation potential.

- Civil-Military Collaboration and Territorial Recovery

A hallmark of Traoré’s governance has been the integration of security and social development. Under his leadership, the Burkinabè military has been restructured into a multi-dimensional force—combining combat readiness with civic engagement.

Key innovations include:

- Creation of the “Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland” (VDP)—a civilian auxiliary force trained and armed to defend local communities

- Deployment of mobile brigades that secure zones while delivering food, medicine, and educational kits

- Establishment of community governance units in liberated areas to rebuild public trust and restart local services

- Partnership with religious and traditional leaders to combat radicalization through culturally rooted deradicalization campaigns

In 2024, the government had reportedly reopened over 800 rural schools, rehabilitated 400+ km of roads, and reinstated local government presence in more than 50 previously inaccessible zones (Burkina Ministry of Territorial Administration, 2024).

- Participatory Governance: The People’s Assemblies and Youth Mobilization

Unlike typical military juntas, Traoré’s STM-inspired model seeks popular endorsement beyond the barracks. Town-hall-style forums, known as People’s Assemblies, are held regularly to gather local input on national policies. Citizens have participated in:

- Drafting the transitional constitutional charter

- Debating the future shape of Burkina Faso’s state (federalism vs. centralism)

- Suggesting budget priorities and anti-corruption mechanisms

Youth and women’s groups have been instrumentalized as agents of transformation. National civic corps, youth brigades, and women’s farming cooperatives are supported through seed funding, training, and state purchases of local produce. Traoré has repeatedly emphasized that “sovereignty begins with food, dignity, and discipline, not slogans,” signaling a commitment to empowerment over propaganda.

- Educational and Spiritual Renewal

Education reform in Burkina Faso under Traoré is not just about curriculum content, but about philosophical realignment. The Ministry of Education has initiated:

- Incorporation of local languages in primary education

- Curriculum reorientation toward agriculture, self-reliance, and African history

- Partnership with Islamic and traditional institutions to rebuild ethical and moral foundations

- Expansion of technical and vocational training aligned with national needs

This spiritual and epistemological transformation aligns with Thomas Sankara’s legacy, while addressing the identity vacuum left by years of imported pedagogy and cultural alienation.

- Public Reception and International Response

Internally, Traoré commands widespread support, particularly among rural communities, university students, and traditional leaders. Public demonstrations often celebrate national milestones such as debt cancellation or the reopening of schools. Internationally, however, the response is more mixed. While ECOWAS, the African Union, and the EU have raised concerns over democratic backsliding, ordinary Africans across the continent have hailed Burkina Faso as a symbol of African pride and self-assertion. Some nations are exploring bilateral cooperation outside ECOWAS structures.

- A Work in Progress: Achievements and Caveats

While Traoré’s STM-oriented reforms have yielded tangible outcomes, the road ahead remains challenging. Risks include:

- Economic isolation and retaliatory sanctions

- Over-reliance on military logic in governance

- Potential erosion of civil liberties if security remains the dominant narrative

- Intra-elite fragmentation and succession uncertainty

Nonetheless, Burkina Faso’s case demonstrates that another form of governance is not only possible but already underway—one that privileges sovereignty, dignity, and purpose over compliance with externally defined legitimacy.

- Risks and Realities: Critical Appraisal of the Sahelian Transition Model (STM)

- Between Promise and Peril

The Sahelian Transition Model (STM) has undoubtedly invigorated a fresh wave of political imagination across the African continent. As an emerging paradigm that reclaims sovereignty, rejects dependency, and re-engages citizens in state-building, the STM offers a bold corrective to the failures of imported governance models. However, like all experiments in statecraft—particularly those born from transitional military rule—it carries inherent risks. Charismatic leadership, revolutionary fervor, and ideological purity may capture the spirit of the moment, but they do not inherently translate into long-term institutional sustainability. This section explores the critical vulnerabilities of the STM and identifies the conditions under which its transformative promise could unravel.

- The Risks of Militarized Governance

A defining characteristic of the STM is the central role played by the military in both state administration and social engineering. While this has enabled rapid responses to insecurity and facilitated national coordination in crisis-stricken territories, it also introduces risks associated with the overextension of military authority. Civil-military fusion, without adequate accountability frameworks, can lead to the concentration of power in the hands of a narrow ruling elite. Over time, narratives of military heroism may entrench a savior complex that immunizes leadership from criticism and insulates it from public scrutiny. History offers many cautionary tales—from Acheampong’s Ghana to Abacha’s Nigeria—where initially popular military regimes devolved into personalized, repressive systems. Without structural checks, the STM risks hardening into a benevolent authoritarianism, where governance becomes synonymous with command and control rather than rule-based legitimacy.

- Prolonged Transition and Institutional Ambiguity

A recurring concern within STM states is the lack of clarity surrounding transition timelines, governance frameworks, and succession planning. While transitional charters have been adopted to guide national renewal, delays in setting firm electoral roadmaps and hesitations around codifying power-sharing structures risk transforming temporary regimes into permanent arrangements. The prolonged use of “consultative processes” without tangible institutionalization may create what some analysts call transitional stagnation—a liminal space where governance is improvised rather than constitutionally grounded. As transitions drag on, the initial enthusiasm of citizens could give way to skepticism and political fatigue, especially if reforms are perceived as arbitrary or unevenly implemented.

- Economic Fragility and Strategic Dependencies

Although the STM’s economic philosophy—rooted in sovereignty, self-reliance, and debt rejection—has resonated deeply with many African constituencies, its short-term implications are complex. Turning away from Western financial institutions and global capital markets restricts access to development financing and may destabilize foreign exchange reserves. Moreover, emerging partnerships with non-Western actors such as Russia, China, and Turkey, while framed as alternative alliances, carry their own forms of dependency, particularly when contracts lack transparency or local oversight. In fragile economies like Burkina Faso and Mali, even minor disruptions in global commodity prices or climate-induced agricultural failures can quickly destabilise fiscal planning. For STM states to maintain their independence without slipping into new entanglements, they must diversify their economic strategy beyond bilateral aid, strengthen intra-African trade through frameworks like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), and build resilient local value chains to withstand external shocks.

- The Shrinking of Civic Space and Press Freedom

Despite its emphasis on popular engagement and grassroots consultations, the STM’s operational logic has sometimes been at odds with the principles of civic liberty and media pluralism. Instances of press closures, censorship of foreign outlets, and arrests of dissenting voices have raised concerns about the boundaries of legitimate criticism within STM-led polities. While such actions are often justified as protective measures against propaganda and external destabilisation, they risk fostering a political culture in which dissent is conflated with disloyalty. A sustainable governance model must ensure that the right to question authority, through civil society activism, journalistic inquiry, and opposition discourse, is not stifled under the pretext of patriotism. Otherwise, the STM could replicate the same suppressive patterns it was created to reject.

- Diplomatic Pushback and Regional Isolation

The STM’s rise has been met with sharp responses from both regional and international institutions. ECOWAS, the African Union, and the European Union have condemned the unconstitutional nature of the military-led transitions, imposing sanctions and suspensions. These punitive responses, however, have not succeeded in reversing the STM trajectory; instead, they have accelerated diplomatic fragmentation within West Africa. Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have formed their own cooperative alliance, increasingly distancing themselves from ECOWAS and asserting a new regional logic. While this enhances short-term sovereignty, it could undermine long-term continental unity and erode the collective bargaining capacity of Africa as a bloc. The STM must avoid isolationism by engaging constructively with neighboring states and maintaining Africa-wide dialogue through Pan-African institutions.

- Personalization of Power and the Fragility of Charisma

The STM’s popular appeal is heavily concentrated around its youthful, revolutionary leaders—figures like Captain Ibrahim Traoré in Burkina Faso, Colonel Assimi Goïta in Mali, and General Abdourahamane Tchiani in Niger. These individuals have become embodiments of national renewal, resistance, and hope. Yet the over-reliance on charismatic leadership poses long-term risks. Personalization of power can eclipse institutional building, marginalize other capable actors, and create succession crises when these figures eventually step aside. The STM’s sustainability hinges not on individual brilliance, but on whether it can systematize its vision into a robust framework of participatory governance, legal safeguards, and civic education. As Thomas Sankara cautioned, revolutionary soldiers must be guided by political clarity, not blind obedience or populist euphoria.

- Defining and Measuring Success

For the STM to evolve from a transitional phenomenon into a durable model of governance, it must define what success looks like and how it is measured. Tangible achievements in education, healthcare, infrastructure, food security, and territorial cohesion must be demonstrable within the next five to ten years. Equally important is the ability to formalize democratic transitions that reflect African realities—not merely copying Western electoral systems, but creating participatory structures rooted in community legitimacy. A balance must be struck between the need for rapid transformation and the imperative of inclusive rule-making. If STM countries can institutionalize civic inclusion, safeguard freedoms, and deliver economic progress while maintaining stability, they may indeed redefine what democratic legitimacy looks like in the African context.

- The Fragile Triumph of Self-Assertion

The Sahelian Transition Model is a courageous attempt to reclaim the political, economic, and cultural agency that has eluded many African states since independence. It is not perfect, but it is profoundly necessary. Yet its fragility cannot be overlooked. Without institutionalization, legal safeguards, and regional cooperation, the model could easily descend into the very authoritarianism and dependency it seeks to resist. However, if guided wisely—anchored in civic consciousness, pluralism, and resilience—the STM may well represent Africa’s most authentic contribution to 21st-century political thought: a governance system that is neither Western nor imposed, but genuinely sovereign and people-driven.

6. Policy Implications and the Future of African Governance

6.1 Reclaiming the Narrative: From Mimicry to Self-Definition

For over half a century, African governance has been assessed through the lens of external models—whether liberal democracy, socialist centralism, or neoliberal structural adjustment. These paradigms, while influential, have too often failed to reflect the lived realities, communal traditions, and sovereignty aspirations of African societies. The Sahelian Transition Model (STM) emerges not as a rigid ideological alternative but as a provocative call to recenter African governance discourse around indigenous legitimacy, resource sovereignty, and strategic autonomy. It challenges the default position that democracy must always resemble the Western format to be credible, and instead offers a functional, culturally resonant pathway toward national rebirth. For African policymakers, scholars, and civil society leaders, this is an invitation to redefine governance not by imitation, but by introspection—drawing from history, culture, and local governance systems that long preceded colonial rule.

6.2 Extracting Lessons Without Exporting a Template

It is important to emphasise that the STM is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Its origins in military-led transition, its context of insurgency and instability, and its current evolution are unique to the Sahel. Nevertheless, it offers valuable lessons that can be adapted to other African states, particularly those grappling with post-electoral legitimacy crises, economic dependence, and elite disengagement. Key takeaways include the potential to restore public confidence in governance through direct community engagement, resource control policies, civic-military collaboration for development, and educational reform rooted in African identity. Countries such as Guinea, Chad, Sudan, and the Central African Republic—each in different stages of political flux—could study aspects of the STM to inform their transitional frameworks, provided local contexts are prioritised and civilian transitions remain central.

6.3 Rethinking Sovereignty in the 21st Century

A major implication of the STM is its demand for a new African understanding of sovereignty, not just as a legal or territorial concept, but as economic, digital, epistemic, and military control over one’s future. In the STM, sovereignty is operationalised through control of national resources, rejection of illegitimate debt, limitation of foreign military presence, and cultural reassertion. For other African states, embracing sovereignty may mean renegotiating exploitative trade agreements, investing in domestic industrial capacity, and developing cybersecurity architecture that protects African data from extractive surveillance by external actors. It may also involve revising how elections are funded and conducted, limiting dependency on international election observers and donors who wield disproportionate influence over African transitions. Sovereignty, in this frame, becomes not isolationism, but self-governance rooted in dignity and partnership.

6.4 Regional Cooperation and Pan-African Alignment

While the STM has fostered intra-Sahel solidarity through new alliances like the Burkina-Mali-Niger bloc, it also poses questions about the future of continental unity and integration. Africa must avoid a scenario in which successful sovereign states isolate themselves in geopolitical silos, weakening platforms like ECOWAS and the African Union. Instead, STM-inclined nations should reform rather than abandon regional institutions, pushing for greater autonomy from foreign influence and stronger enforcement of intra-African development commitments. A reformed African Union could adopt a multi-model governance tolerance framework, recognising that democracy may take different institutional forms across the continent while upholding shared principles of human dignity, justice, and development. Pan-African economic integration should remain a central goal, with STM states contributing to AfCFTA by investing in cross-border trade infrastructure, energy corridors, and digital interconnectivity.

6.5 Designing an Africanized Governance Model: Strategic Recommendations

For the STM to inspire a broader Africanized governance approach, five strategic pathways must be pursued. First, constitutional reforms should reflect local realities, incorporating traditional authorities, religious leaders, youth, and women into formal governance structures—not as symbolic appendages, but as co-decision-makers. Second, a framework for resource federalism can be developed, allowing regions to retain a fair share of resource earnings while contributing to national budgets transparently. Third, a Sovereign Development Index (SDI) should be introduced to measure African governance success not just by elections or press freedom, but by criteria such as debt independence, local industrial output, citizen participation in governance, and retention of resource revenues. Fourth, national service programs like Burkina Faso’s Civilian Development Corps could be adapted continentally to unify youth around public service, vocational training, and community regeneration. Finally, African education systems must shift from colonial content delivery to critical, Afrocentric, and vocational pedagogy, empowering the next generation to imagine and lead on their own terms.

6.6 Avoiding Pitfalls: The Need for Guardrails and Safeguards

The STM’s future viability, whether in the Sahel or as an inspiration elsewhere, depends on its ability to institutionalise checks and balances. Military-led transitions must self-limit their duration, establish consultative constitutional commissions, and commit to legalising succession plans to avoid coups becoming permanent regimes. Civic space must be protected, with independent media and legal institutions guaranteed freedom to operate without fear or cooptation. Moreover, STM-inspired governance must resist personality cults and the myth of the irreplaceable leader. Governance must be built around enduring systems, not heroic figures. Regional and continental organisations, especially the African Union, should develop transitional governance protocols tailored to African contexts, supporting STM countries in their reform efforts while holding them accountable to shared African values.

6.7 A New Chapter in African Political Innovation

The Sahelian Transition Model, for all its imperfections and unfinished transitions, may represent the beginning of a new chapter in African political thought—one that moves beyond colonial imitations and externally funded façades. Its lessons must be studied carefully, adapted judiciously, and applied with humility. The African continent does not need to choose between authoritarian stability and democratic disorder. The choice instead lies in building a third path—sovereign, inclusive, and rooted in the lived experiences of African peoples. STM is not an endpoint, but a signal: that the age of governance mimicry may be closing, and a new era of African self-definition—politically, economically, and spiritually—is slowly, courageously, beginning.

7. Conclusion

For much of the post-independence period, Africa’s governance discourse has been confined to a narrow corridor—oscillating between externally prescribed democracy, borrowed authoritarianism, and donor-conditioned technocracy. This corridor has produced systems that often lacked legitimacy, failed to deliver prosperity, and alienated citizens from the very state meant to serve them. The emergence of the Sahelian Transition Model (STM)—forged in the crucible of crisis, popular resistance, and anti-colonial revivalism—signals a radical departure from this trajectory. It invites Africans to rethink not only how they govern but who they are in the act of governance. The STM does not offer a universally replicable framework, nor does it pretend to have all the answers. It is a transitional, evolving system—imperfect and unfinished. But it is precisely in its audacity to challenge neocolonial scripts and affirm endogenous sovereignty that it demands scholarly and political attention. In prioritising territorial integrity, resource nationalism, civic mobilisation, and epistemic dignity, STM countries are attempting to complete the decolonisation project that formal independence left unresolved.

This model reclaims the political vision of Africa’s foundational thinkers. Kwame Nkrumah’s dream of political and economic liberation, Thomas Sankara’s ethics of service and accountability, Muammar Gaddafi’s pan-African solidarity, and Nelson Mandela’s pursuit of justice and reconciliation are embedded in the philosophical DNA of the STM. These leaders, though maligned or martyred in different ways, foreshadowed the need for a uniquely African pathway to power—one rooted not in mimicry but in mastery. Yet, the road ahead is narrow and fraught. Without robust institutions, STM may become susceptible to the very autocracy it seeks to transcend. Without civic freedoms and legal protections, the promise of people’s power may be co-opted by force of arms. And without regional alignment and economic diversification, the threat of isolation or capture by new external actors looms large. Thus, African sovereignty must be both assertive and accountable, both locally defined and globally strategic.

What the STM offers, then, is not a doctrine, but a provocation. It challenges the continent to imagine governance not as an imported performance for global validation, but as a practical expression of collective will, cultural memory, and visionary leadership. It reminds us that freedom is not given through ballots alone, but earned through structural transformation, ideological clarity, and ethical resolve. As the Sahel experiments with a new political future, it may be planting the seeds of a continental renaissance—a quiet revolution not televised by foreign media or funded by global foundations, but authored by the very people who, for too long, have been told how to govern, how to think, and how to serve. In reclaiming their destiny, they may be leading all of Africa into a new epoch—one where sovereignty is not just a flag or anthem, but a lived reality rooted in justice, dignity, and self-determination.

*******

Dr David King Boison, a maritime and port expert, AI Consultant and Senior Fellow CIMAG. He can be contacted via email at [email protected]

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

- President Commissions 36.5 Million Dollars Hospital In The Tain District

- You Will Not Go Free For Killing An Hard Working MP – Akufo-Addo To MP’s Killer

- I Will Lead You To Victory – Ato Forson Assures NDC Supporters

Visit Our Social Media for More