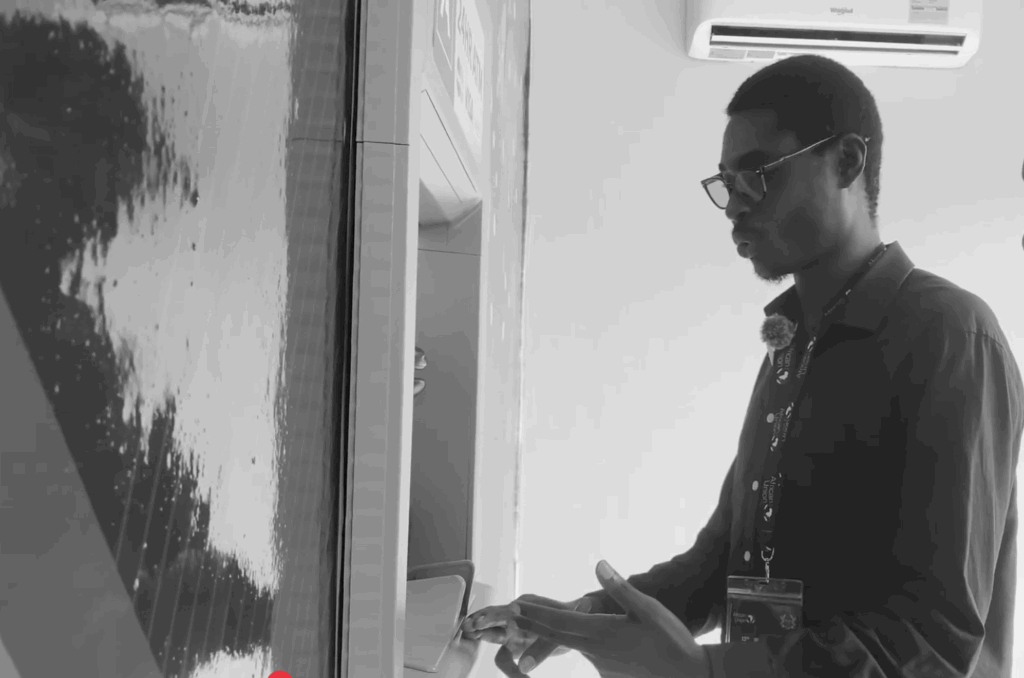

On a cold Sunday afternoon in Accra, Moro Ibrahim stands in front of an ATM that many Ghanaians use without a second thought. But for him, the simple act of withdrawing money becomes an impossible task.

The machine has no voice automation, no tactile labels, and no accessibility features. “I don’t know which one is one. I don’t know which one is two,” he says, running his fingers helplessly over the keypad. Without speech guidance, he adds, “It’s not going to be possible for me to access it.”

Moro’s struggle is not an isolated inconvenience—it’s evidence of a deeper problem within Ghana’s rapidly expanding digital financial ecosystem. As banks and fintech platforms race ahead with modern tools, many citizens with disabilities remain stuck behind invisible barriers that technology has failed to break.

Moro Ibrahim, visually impaired struggling behind the ATM

When digital infrastructure excludes instead of empowering

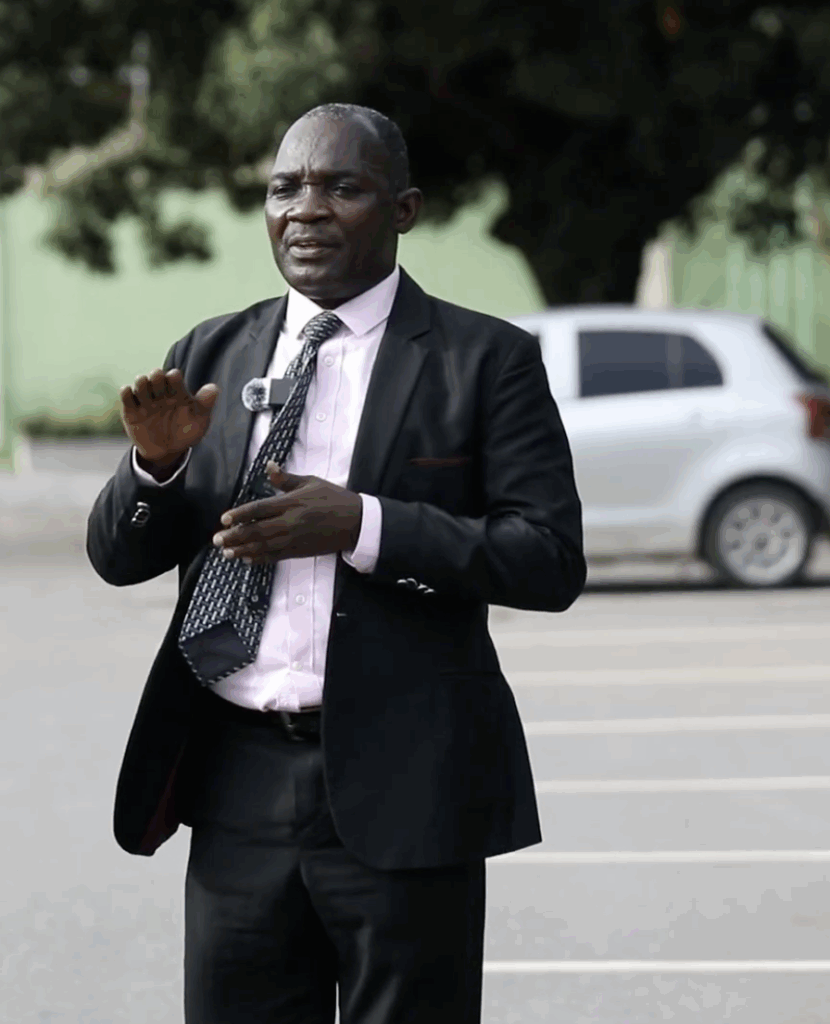

Ghana’s digital transformation of mobile money systems, biometric IDs, and online banking promises to simplify life. But as development economist Dr Hayford Mensah Ayerakwa of the University of Ghana explains, the promise is incomplete.

“ATMs should be friendly to all manner of persons,” he says. “But banks are profit-making businesses. If we don’t enforce the rules, they will turn a blind eye.”

The Bank of Ghana has policies that require accessible ATMs and disability-friendly service points. Yet implementation remains weak. Dr Ayerakwa argues that the regulator’s limited enforcement capacity allows banks to deprioritise accessibility. Even inside banking halls, he notes, staff often lack training to support people with specialised needs.

“Inclusion isn’t just at the ATM,” he says. “It’s at different points within the banking pool.”

Dr. Hayford Ayerakwa, Development Economist

“It is totally not accessible”: Life without accessible banking tools

For people like Moro, the absence of voice-guided machines means constant dependence on others—something that compromises security and dignity.

“Even if I struggle to use it, the voice is coming out so a third party can hear whatever I’m trying to do,” he explains. With no option for a headset or privacy settings, entering a PIN becomes a public act. As a result, Moro avoids ATMs altogether unless someone assists him.

“If I’m a client, the bank should train me,” he says. “But there is nothing like that. They just leave you to your fate.”

The result is financial exclusion, an outcome that digital public infrastructure was supposed to eliminate.

For Wheelchair Users, Banking Begins With a Physical Battle

At his home, entrepreneur Alex Tetteh reflects on another layer of exclusion: the physical world. Many banking halls lack ramps, accessible counters, or automatic doors.

“Physical barriers are a huge thing,” he says. “As an entrepreneur, you need to move from office to office… It’s very, very difficult.”

Alex leads the Ghana Chamber for Entrepreneurs with Disabilities, representing business owners across 13 regions. For people with mobility impairments, he says, digital innovations have helped—but only to a point.

“Yes, the digital space has lessened challenges,” he acknowledges.

“But it has opened up another aspect of challenges, how persons with disabilities navigate and access these digital products.”

Beyond mobility issues, he describes long-standing biases: clients who bypass him because they don’t expect a person in a wheelchair to be the boss, staff who doubt disabled entrepreneurs’ ability to manage money, and banks that hesitate to offer credit.

The problem is not only physical, but it’s also attitudinal.

Alex Tetteh, Ghana Chamber for Entrepreneurs with Disabilities

“They forget the deaf”

While ramps and wider doors matter, Robert Frimpong Manso, a professional sign language interpreter, says the deaf community faces a completely different kind of exclusion.

“Deaf people are almost always forgotten,” he explains. When banks design service points, they often assume the needs of all disabled customers are the same. “They will mount ramps, showing that they consider the disabled. But they forget that among the disabled, there are some groups called deaf, who don’t need ramps.”

What they need is communication.

Inside banking halls, information screens roll with text and voiceovers, neither of which fully serves deaf clients. Some deaf people can read; many struggle with written English, since sign language is their primary language. Without interpreters or visual communication guides, banking becomes a guessing game.

Announcements like “Teller 1… next customer” go unheard. Registration for mobile money accounts requires answering verbal questions. Vendors don’t understand sign language.

So, deaf customers must involve third parties in private financial transactions.

“That’s certainly not secure,” Mr Frimpong Manso stresses.

Before leaving, he interprets his thoughts directly to the deaf community:

“They struggle before they access information. We need to assist them so they can access whatever information is given to the general public.”

Robert Frimpong Manso, professional sign language interpreter

Digital public infrastructure: A bridge or a wall?

Ghana’s ambition for a modern digital economy is clear. But the foundational principle of digital public infrastructure, universal access, is not being met.

For the visually impaired, the absence of accessible ATMs turns financial autonomy into a dream.

For wheelchair users, inaccessible buildings and systemic bias remain daily hurdles.

For the deaf, banking systems built around sound shut them out entirely.

Each of these experiences reveals the same truth: a digital system that excludes is not digital progress—it is digital inequality.

- President Commissions 36.5 Million Dollars Hospital In The Tain District

- You Will Not Go Free For Killing An Hard Working MP – Akufo-Addo To MP’s Killer

- I Will Lead You To Victory – Ato Forson Assures NDC Supporters

Visit Our Social Media for More