Why Africa’s next wealth frontier will be ocean intelligence, not ocean transport

For most of human history, the wealth of nations has been written first in the soil, then in the sky, and now increasingly in the sea. The industrial age rose on the back of minerals dug from the ground. The digital age accelerated through capabilities harvested from space, especially satellites, navigation, timing and Earth observation. The next age, still forming, will be driven by what the ocean can yield, not only as a shipping lane, but as an engine of minerals, energy, medicine, climate services and biological invention.

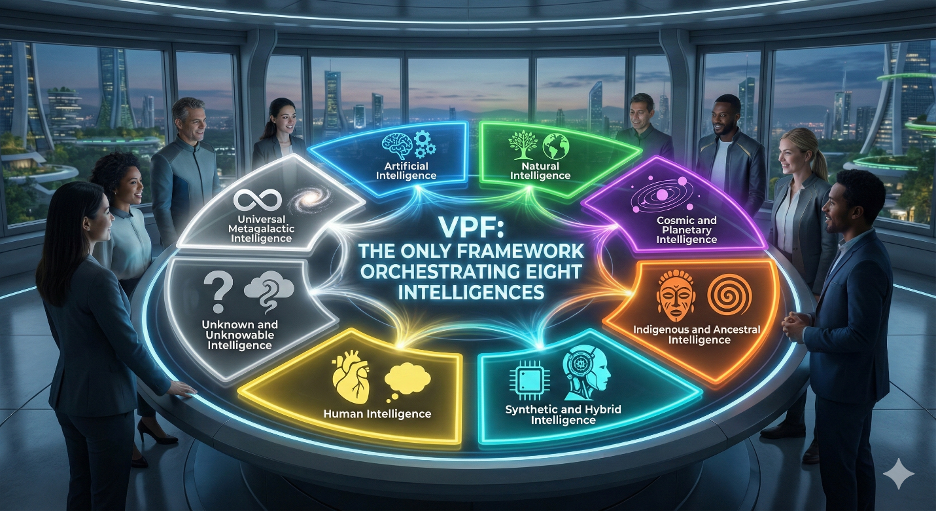

The blind spot is that we are trying to enter this next age with powerful yet incomplete tools. Conventional AI can process maritime data streams, forecast congestion, and optimise routes. Yet it struggles to interpret the deeper systems that govern oceans, because oceans are not merely datasets. They are living, multi-layered systems with ecological logic, historical memory, cultural custodianship and long-cycle feedback loops that ordinary AI does not “understand” in any wise sense. The Visionary Prompt Framework, VPF, reintroduces what modern automation left behind by structuring intelligence as plural. It brings Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence back into the room, and it restores Natural Intelligence as a first-class source of truth about the sea. This is the difference between managing ships and mastering the ocean economy.

What minerals in the soil have already given humanity

When we speak about minerals in the soil, we are not speaking about “commodities” in the abstract. We are speaking about the physical foundation of civilisation: copper for electrification, iron ore for steel, limestone for cement, bauxite for aluminium, and a fast-growing set of “critical minerals” that now sit inside batteries, semiconductors, wind turbines, and advanced defence systems. If you strip the world of minerals, you strip it of modern infrastructure.

The clearest evidence of this mineral dependence is not philosophical. It is economic and strategic. The World Bank’s work on extractive industries notes that demand for key minerals such as copper, lithium, graphite, nickel and rare earth elements is expected to nearly double by 2040, implying a new mining investment wave measured in hundreds of billions of dollars and a broader multi-trillion-dollar buildout across mining, processing and related infrastructure by mid-century (World Bank, 2025). This is a statement about the soil’s continuing role in the next industrial transition, not the last one.

The United States Geological Survey’s Mineral Commodity Summaries is one of the standard annual references governments and industry use to track production, reserves, and world supply conditions across more than 90 nonfuel mineral commodities, precisely because minerals remain the backbone of modern production systems (U.S. Geological Survey, 2025). Even when countries transition toward “green” economies, mineral intensity does not vanish. It changes form. Oil dependency declines, but demand for metals that enable electrification rises.

For Africa, this reality is both an opportunity and a warning. Opportunity, because the continent holds significant shares of several minerals crucial to energy transition supply chains. Warning: the historical pattern has been the export of raw ore and the import of finished products. The soil has given Africa resources; global systems have often captured the downstream wealth. That is why the next frontier, the ocean, must be approached differently, with sovereignty of interpretation, not only sovereignty of territory.

What space has already given humanity, and why it matters for ocean wealth

Space is no longer a romantic frontier. It is an economic infrastructure layer. The modern world runs on satellites that enable communications, weather forecasting, Earth observation, mapping, disaster response, banking time synchronisation, and precision navigation. If satellites went dark, ports would slow, ships would lose routing optimisation, insurance risk models would degrade, and coastal security monitoring would become blind.

The numbers reveal how large this has become. The Satellite Industry Association reported that the overall global space economy generated about 400 billion dollars in revenue in 2023, with the commercial satellite industry accounting for a dominant share of that activity (Satellite Industry Association, 2024). Another major tracking institution, the Space Foundation, estimated the global space economy at 570 billion dollars in 2023, driven largely by commercial revenues (Space Foundation, 2024). Differences between estimates reflect methodological differences, but the strategic signal remains consistent. Space is already a major economic layer.

What matters for ocean strategy is that space has become the nervous system for maritime visibility. Satellite-based AIS supports vessel tracking. Earth observation supports coastal erosion monitoring. Weather satellites support storm prediction. Remote sensing supports fisheries surveillance and the detection of illegal fishing patterns. In other words, space has already been “given” to the ocean economy. This is why maritime systems can now be monitored at scale.

It also shows the direction of future value. The World Economic Forum has estimated that the space economy will grow from roughly 630 billion dollars in 2023 to about 1.8 trillion dollars by 2035, reflecting how space-enabled services increasingly underpin other industries (World Economic Forum, 2024). For Africa, the lesson is sharp. When you do not own the infrastructure layer, you pay perpetual rent. That same pattern now threatens to repeat at sea, if Africa treats the ocean only as transport and leaves discovery, mining, biotechnology and data sovereignty to others.

What the ocean can give us that we do not fully know yet

The ocean is the last great frontier of unknown value because its mapping, biology, mineral systems and deep ecology remain largely unexplored. A widely cited scientific reality is that only a minority of the seabed has been comprehensively mapped at high resolution, leaving huge uncertainty about the scale and distribution of deep-sea resources and ecosystems. This unknown is precisely where future wealth hides.

One of the clearest “known unknowns” is the potential for seabed minerals. Polymetallic nodules, cobalt-rich crusts, and seafloor massive sulfides are not speculative myths. They are documented geological realities. What remains uncertain is the full scale, the economically recoverable portion, and the long-term ecological costs and governance structures required to extract them responsibly.

Peer-reviewed work on polymetallic nodule deposits has produced quantitative resource estimates that are not trivial. One study estimating resources in the Clarion–Clipperton Zone reported total nodule resources on the order of hundreds of millions of tonnes of dry nodules, with metal contents measured in millions of tonnes for manganese, nickel, copper, and cobalt, as well as rare earth elements (Kuhn et al., 2021). This is the kind of resource scale that attracts strategic competition, as nickel and cobalt are central to battery supply chains and advanced manufacturing.

International Seabed Authority technical materials also emphasise that polymetallic nodules contain nickel, cobalt, manganese, and copper, and occur across oceans, with particularly well-known deposits in the Clarion–Clipperton Fracture Zone (International Seabed Authority, 2022). Independent techno-economic literature has argued that, for some metals, the metal content in certain nodule provinces could be comparable to or exceed known terrestrial reserves, which is why deep-sea mining debates have become so intense globally (Van Nijen et al., 2018). The point is not that extraction is automatically good. The point is that the ocean’s mineral story is large enough to change geopolitical and industrial trajectories.

But minerals are only one layer. The ocean’s biological and biochemical potential may be even more disruptive. Marine organisms survive pressures, temperatures, and chemical environments that would kill most terrestrial life. Those survival mechanisms are biochemical libraries. They can translate into new enzymes for industry, new compounds for pharmaceuticals, new biomaterials, and new genetic insights. The deep sea is not only a mine. It is a laboratory.

Then there is energy. Wave power, tidal power, offshore wind integration, ocean thermal energy conversion, and even salt-gradient energy all represent underexploited systems. Add to that blue carbon, especially mangroves and seagrasses, which store carbon at high density and can be monetised through credible carbon markets if governance is strong. This is where African ports can evolve from container nodes into climate-finance and ecosystem-service hubs, turning coastlines into national balance-sheet assets rather than unmanaged edges.

This is the correct claim: the ocean can give Africa far more than transport revenue, but much of that value remains unknown because discovery systems, research funding, and industrial pathways have not been built at scale across African maritime states.

Unearthing ocean value with VPF: why plural intelligence is the missing tool

The economic tragedy is not that Africa lacks ocean assets. It is that Africa often lacks an integrated intelligence architecture for converting ocean complexity into sovereign wealth without ecological collapse. This is where VPF becomes practical.

Conventional AI is useful for prediction and optimization. It can cluster satellite imagery, detect vessel anomalies, forecast berthing congestion, and model trade flows. But the ocean is not a stable, closed system. It is an adaptive system. Its value is entangled with ecology, community livelihoods, sacred geographies, seasonal cycles, and climate feedback loops. AI can carry “data” about these things, but it does not naturally carry wisdom about what to preserve, what to protect, what to never disturb, and what to treat as a living partner rather than a commodity store.

VPF’s Natural Intelligence Chamber forces maritime planning to start with the ocean as a system that self-organises. It makes port development accountable to tidal flows, sediment dynamics, mangrove nurseries, coral protection, and long-horizon climate risk. Under this chamber, “growth” is not measured only in throughput. It is measured in resilience, biodiversity retention, flood-risk reduction, and the stability of fisheries that feed cities.

VPF’s Indigenous and Ancestral Intelligence Chamber restores long-memory datasets. Coastal elders and fishing communities become sources of time-series knowledge that often predates modern measurement. Their navigation patterns, taboo zones, seasonal calendars, and storm heuristics become inputs for governance and science. This is not a ceremonial gesture. It is a practical upgrade, because oral ecological knowledge often encodes real signals that formal systems miss, especially in data-sparse environments.

When VPF integrates these with Artificial Intelligence and Human operational intelligence, a new capability emerges. Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Cameroon and other African maritime states can build ocean intelligence stacks that combine satellite sensing with community-grounded validation, ecological modelling with cultural constraints, and industrial ambition with long-term stewardship. That is how Africa avoids repeating the soil story, in which raw wealth was exported and downstream value imported.

If Africa approaches the ocean with VPF, it does not merely ask, “What can we ship through the sea?” It asks, “What can the sea teach us, give us, and sustain for centuries?” That question is the doorway to wealth that does not collapse its own foundation.

******

Dr David King Boison is a Maritime and Port Expert, pioneering AI strategist, educator, and creator of the Visionary Prompt Framework (VPF), driving Africa’s transformation in the Fourth and Fifth Industrial Revolutions. Author of The Ghana AI Prompt Bible, The Nigeria AI Prompt Bible, and advanced guides on AI in finance and procurement, He champions practical, accessible AI adoption. As head of the AiAfrica Training Project, he has trained over 2.3 million people across 15 countries toward his target of 11 million by 2028. He urges leaders to embrace prompt engineering and intelligence orchestration as the next frontier of competitiveness. He can be contacted via email at [email protected], on cell phone: +233 20 769 6296; or you can visit https://aiafriqca.com/

- President Commissions 36.5 Million Dollars Hospital In The Tain District

- You Will Not Go Free For Killing An Hard Working MP – Akufo-Addo To MP’s Killer

- I Will Lead You To Victory – Ato Forson Assures NDC Supporters

Visit Our Social Media for More