Not too long ago, I managed the nation’s biggest media organisation by all measures: by footprint, infrastructure and human resources. It was routine for me to meet my senior editorial team on matters of strategy and operations. In one such encounter, I threw a question at the team. “In the unlikely event, touch wood, that the president passes today, what is our protocol for breaking the news”? The room was silent.

The kind of silence that is difficult to decipher because it oscillates between discomfort and incredulity. I even felt a few eyes silently accusing me of wishing death for the president. When it became clear to me that no known protocol existed, I asked that the matter be discussed further and a formal protocol established, including keeping an updated archival material of the president, vice president, and the heads of the other arms of government.

I also directed that radio, television and online simulate such breaking news scenarios every once in a while, to ensure that the protocol was robust and everyone in the circuit was on the same page. As it became clear later, I was neither wishing death for the president at the time nor a calamity to befall the

country. I was prodding a sensitive subject: how do we, as a foremost media organisation, break sensitive news in a time of national crisis in a manner that dignifies the subject, our profession and upholds public sensibilities?

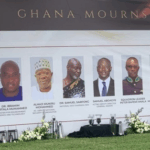

I have found myself tossing this exact question in my head over the past 24 hours. It’s 12:14 pm on Wednesday, August 6, 2025. A nation is gripped in grief at the passing of 8 of its citizens, all in the line of national duty. Details from the very onset were sketchy, and the rumour mill was grinding at full throttle. The eight are feared dead after the helicopter they were travelling on crashed and burst into flames. Snippets of information crept through the air as social media led the orgy of showing gruesome images of the accident, with television and radio trying hard to catch up.

From the period of the official announcement of the accident to when the remains arrived at the Air Force base in Accra, viewers were subjected to some of the most insensitive and gruesome coverage of the deceased in living memory.

One radio station had a couple of its lead presenters discuss the incident with very personal stories. The personal stories and anecdotes they shared humanised the deceased and framed them as diligent, heroic public servants whose love for their nation had exacted from them the ultimate price of losing their lives. On another station, the wife of one of the deceased was shown in graphic detail, wailing uncontrollably as other family members tried to restrain her. I caught myself asking if there is a line between the private and the public here, and whether the introduction of the camera into such private, even intimate spaces doesn’t impose responsibilities on media practitioners?

Then I switch to another (television) station where a reporter is close to the site of the crash, conducting interviews. It is this episode that I wish to focus on. The reporter is asking an official if he “can confirm whether the bodies had indeed been conveyed in sacks”! The interviewee responds in the affirmative. As the interview proceeded, the interviewer kept dwelling on the fact that the bodies were carried in sacks, and went as far as showing in a medium close-up, a sack that one of the bearers had on his head as he navigated the treacherous terrain. What is going on here, I asked myself?

Then he asks the interviewee if he saw the charred bodies. His next question, when the interviewee confirms that he had indeed seen the bodies, was that he describes the badly damaged bodies! The interviewee calmly declined. All through this interview, the reporter and his camera operator never missed an opportunity to pan, zoom in or tilt up or down, to show any passer-by who carried a sack. It was at this point that I called some of my colleagues in the media to complain about what I had observed and asked one senior editor to rein in the reporter who worked at his station.

This report and many others raise important questions about journalism ethics and how reporters from newsrooms are to conduct themselves when dealing with disasters and persons in grief. I am, for now, excluding those social media influencers and bloggers who shamelessly shared gut-wrenching images of burning bodies on social media. They are a subject to be addressed another day. For our reporter, decency and respect for the deceased and their families demanded that he and his camera operator exercise some caution, if for nothing at all.

I am still struggling to understand how a story is significantly enhanced by showing the jute sack containing the charred remains of a deceased human being in medium close-up. Must it be shown? What does the reporter hope to achieve by asking an interviewee to describe “badly damaged body parts” he witnessed? Is the intent to shock, scandalise or better inform us? I can understand the craze to be the first to report. What I cannot come to terms with is the insensitivity and lack of decorum that accompany such an enterprise.

Flowing from this, I encourage editors of newsrooms to have in place a tried and tested protocol of covering “breaking news”. Additionally, they should pay more attention to the reporters they send on site to report on such sensitive beats. More senior reporters, through long service and personal experience, tend to have the right temperament and inclination to cover such beats. If a more senior reporter is not handy due to the circumstances, then I suggest that reporters on such beats are equipped with detailed, pragmatic guidelines of what to do and what to avoid.

This is necessitated by the fact that such a reporter on location performs the triple functions of a live reporter, a video editor and a gatekeeper, assuming the additional function of his/her editor momentarily. A more experienced cameraperson could be a real asset in this case, focusing on what is needful and avoiding the spectacular, especially when it is of the kind that adds nothing to the story, but offends the sensibilities of viewers.

After all, the 1994 version of GJA’s code of ethics enjoins journalists “in cases of personal grief, distress, to exercise tact and diplomacy in seeking information and publishing” (Article 16). Let me conclude by inviting television reporters and their crew to chew over this observation by Stephenson and Debrix (1976). They rightly point out that “in the real world, vision is controlled by attention, but in the cinema [television] it is the other way round: attention is controlled by vision.

In everyday life, we see what we attend to; in the cinema, we attend to what we see – that is, what the film director chooses to show us. […] It is part of the filmmaker’s art to determine what the viewer will see. That is the difference between art and reality” (Cinema as Art, 1976: 81). This duty is a burden all television reporters and their camera persons should carry with great care and expertise. Let us remember that the art of framing goes beyond what is captured. It also includes what is omitted. May the souls of our gallant Ghanaian brothers rest in peace.

Dr Kwame Akuffo Anoff-Ntow

Accra, Ghana

7 August, 2025

- President Commissions 36.5 Million Dollars Hospital In The Tain District

- You Will Not Go Free For Killing An Hard Working MP – Akufo-Addo To MP’s Killer

- I Will Lead You To Victory – Ato Forson Assures NDC Supporters

Visit Our Social Media for More